Not all damage is death. Not every flaw is a failure. But there are times—even in the romantic world of vintage jewels—when a piece is, quite simply, beyond saving.

Restoration is at the heart of what we do at Grygorian Gallery. But every jeweler must sometimes look a client in the eye and gently say: We cannot bring this back—not without compromising its integrity, its heritage, or its soul.

This guide is not about despair. It is about knowledge—knowing when to restore, when to transform, and when to let go.

The Body: When Metal Can No Longer Hold Its Shape

Time has its own metallurgy. Over decades—sometimes centuries—precious metals undergo microscopic changes. Gold, especially in antique low-karat forms, can suffer from porosity: tiny holes from poor casting or years of exposure to moisture and skin oils. Platinum, though strong, can experience stress fractures, particularly in delicate Edwardian settings with pierced filigree. Silver, often used in Georgian mountings, oxidizes and becomes brittle in its joints, especially when repeatedly exposed to incorrect polishing techniques or humidity.

In these cases, repairs may be possible in isolation. But when metal fatigue is widespread—when entire shanks begin to crack, brooch mechanisms collapse, or links crumble with the gentlest pressure—each repair adds tension to a body already collapsing. We must ask: are we preserving a jewel, or merely stitching together its remains?

The Soul: When Gemstones Speak of Irreversible Damage

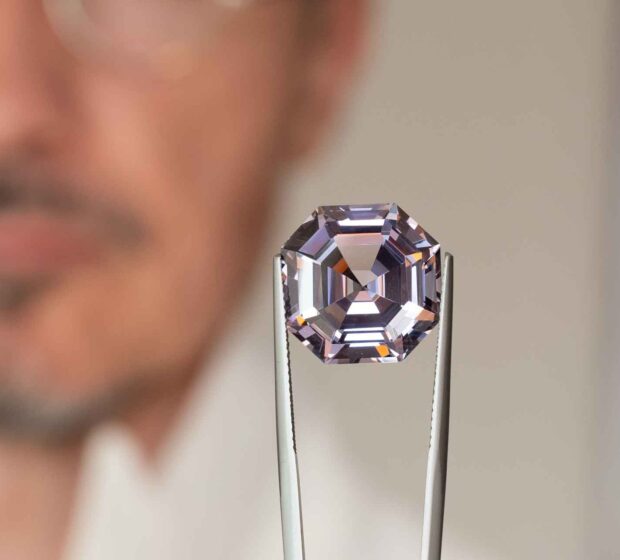

No element of a vintage jewel is more visibly vulnerable than its stones. Diamonds, though hard, can cleave along perfect lines if struck just right. Emeralds—beautiful but brittle—may carry within them feathered fractures that widen imperceptibly with each generation. Pearls may dry, crack, or even rot from the inside if improperly stored. Opals may craze, developing surface cracks from sudden humidity shifts or age alone.

We often see stones that appear intact but fluoresce with damage under a loupe or microscope. Internal fissures, shattered girdles, or abraded facets on soft gems like garnets or spinels all signal risk. And while minor polishing or repolishing can sometimes renew a gem’s light, overworking the stone strips away more than material—it erases age, character, provenance.

Replacing a center stone is sometimes an option, but if the original cut is rare—such as an old mine or rose cut—it becomes a question of identity. If we replace its heart, is it still the same piece?

The Detail: When Decoration Cannot Be Duplicated

In the world of antique jewelry, the devil—and the magic—is in the detail. Guilloché enamel from the Belle Époque, millegrain edges on a platinum band, hand-chased engraving barely visible to the eye: these flourishes define a piece as much as any gem. But once they are lost, they cannot be authentically recreated.

Enamel, in particular, presents one of the greatest restoration challenges. Most antique enamel work used lead-based formulas and kiln-firing techniques no longer replicable today. Matching not just color but depth, luster, and transparency is nearly impossible. Even a master enameler may find it ethically questionable to attempt a partial reapplication on a surface that has lost its foundation. More often than not, attempting to re-fire or touch up an enamel area results in new cracking or discoloration.

The same is true for filigree—especially Art Deco or Edwardian filigree, which was not cast but pierced and finished by hand. Once damaged or thinned by wear, it cannot be recast without replacing entire sections. A “repaired” filigree ring often becomes a modern homage rather than a true restoration, with new elements welded to the old, altering its lines and soul.

The Past: When Previous Repairs Have Done More Harm Than Good

Many jewels come to us already wounded—not by time, but by well-intentioned but unskilled hands. We often encounter pieces with cold solder joints, cracked stones set too tightly, or entire galleries replaced with mass-produced components. Prongs once hand-fabricated are now thick claws from a modern setting; a Victorian brooch is backed with glue and base metal. These choices, made decades ago or just last year, can irreversibly compromise the integrity of a jewel.

Even worse is abrasive polishing. A single session on the wrong wheel can erase engraved initials, maker’s marks, or centuries-old texture meant to catch the light softly. Hallmarks—those tiny stamps that tell us who, where, and when—vanish, taking provenance with them. And once lost, no amount of appraisal can recreate the story they held.

The Truth: When Restoring Becomes Rebuilding

There is a point at which restoration no longer respects the piece—it rewrites it. When more than half of the original structure, gems, or detailing would need to be replaced, we must ask ourselves: is this still the same jewel, or a modern replica cloaked in sentiment?

Authenticity is not measured by polish. It is measured by what survives untouched. If too much has been replaced, the story is no longer whispered through aged gold and imperfect settings. It becomes a costume—a suggestion of the past, rather than a living part of it.

The Grace: When Transformation Is the Only Honest Path

Yet all is not lost. Pieces beyond saving in their original form often carry enough essence to inspire something new. A shattered Victorian ring might give rise to a pendant that preserves its central diamond. An Edwardian bracelet, crumbled at the clasp, becomes a pair of matching earrings—small echoes of what was once whole.

Transformation is not destruction. It is a creative act guided by memory and intention. When done respectfully, it can extend a jewel’s lineage, allowing it to move forward not in denial of its past, but because of it.

At Grygorian, we often work closely with clients to reimagine what remains. We salvage the heart of a piece—the stones, the motif, the engraving—and help it find a second life, just as personal, just as precious.

The Wisdom: When Letting Go Is the Highest Form of Care

And then there are pieces we do not touch. A brooch cracked through its center but etched with a lover’s inscription. A mourning ring too fragile to wear, but rich in emotional weight. These, we place in velvet boxes, glass domes, shadow frames. Not as jewelry, but as heirlooms. Because not every relic must return to daily life. Some exist to be remembered, not revived.

To declare a piece beyond saving is not to discard it. It is to recognize its dignity—and protect it from indignity. Sometimes, the most expert thing a jeweler can do is nothing. To step back. To preserve silence. To honor decay.

Final Thoughts

Jewelry is not eternal. But meaning is. Each piece that comes through our doors carries not just carats, but character. Our duty is not merely to restore—it is to listen. To feel. To know when the best craftsmanship is restraint. And when we do restore, we do so with reverence.

If you’re holding a piece you’re unsure about—damaged, dulled, or perhaps simply exhausted—submit request to personal consultation. We’ll tell you the truth. Not just whether it can be saved, but whether it should be.

Because here, at Grygorian Gallery, we believe jewelry is more than adornment. Its memory made material. And even memory, sometimes, needs rest.